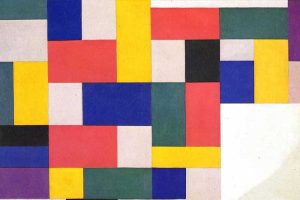

Concrete art is one of the most intriguing movements of the 20th century. Often misunderstood and overshadowed by more emotional styles like Abstract Expressionism, it set out to create a universal language built only from shapes, lines, and colors. More than just a style, it was a bold statement: art should not imitate reality but exist as an independent, concrete fact.

The Paradox of “Concrete”

At first glance, the term concrete art seems confusing. The word “concrete” suggests solidity, tangibility, and materiality. Yet the movement it names is one of the most radical forms of abstraction ever created. Unlike traditional abstract art, which may borrow hints from visible reality, concrete art eliminates all references to the external world. It is an art that exists entirely on its own terms: color, shape, line, and structure. This paradox the tension between the “concrete” and the “abstract” makes the movement one of the most fascinating chapters of 20th-century modernism.

Historical Context: The Early 20th Century

The first decades of the 20th century were marked by extraordinary artistic upheaval. Cubism broke objects into fractured planes. Futurism glorified movement and technology. Suprematism and Constructivism in Russia sought a language of pure geometry. Meanwhile, artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Hilma af Klint moved decisively toward non-representational work, paving the way for deeper abstraction.

-

Kandinsky produced some of the earliest fully abstract paintings, guided by music and spirituality.

-

Malevich shocked the art world with his Black Square (1915), a painting reduced to a single geometric form.

-

Hilma af Klint, long overlooked, created vast symbolic canvases rooted in Theosophy and Hermetic philosophy.

All of these experiments challenged the boundaries of representation. But it was Theo van Doesburg, founder of the Dutch De Stijl movement, who would crystallize these tendencies into a precise definition of concrete art.

Theo van Doesburg and the Manifesto of 1930

In 1930, van Doesburg published The Basis of Concrete Art, a manifesto that gave the movement its name and intellectual foundation. He argued that true art should not imitate nature, tell stories, or symbolize emotions. Instead, it should be “concrete” — constructed from elements that have no external reference, existing purely as visual facts.

This was a bold step even beyond the ideals of De Stijl, which emphasized geometric reduction, vertical and horizontal lines, and primary colors. For van Doesburg, concrete art was not just a style but a philosophy: the belief that painting and sculpture should be autonomous realities, independent of human sentimentality. His ideas resonated with artists across Europe, especially those searching for clarity, universality, and order in the turbulent years between the world wars.

Key Characteristics of Concrete Art

Concrete art is defined by several consistent features:

-

Geometric precision – Circles, squares, grids, and linear compositions dominate.

-

No representation – Unlike abstract art inspired by nature, concrete art avoids external references altogether.

-

Objectivity over subjectivity – Emotion, symbolism, and narrative are excluded.

-

“Cold abstraction” – Works often have a polished, mechanical finish, appearing free from the artist’s hand.

-

Universal language – The aim was to create a visual system that could be understood by anyone, beyond cultural or personal context.

This intellectual rigor made concrete art both admired and criticized: admired for its purity, criticized for its distance from human emotion.

Major Figures of the Movement

Theo van Doesburg

Painter, writer, and architect, van Doesburg was the visionary who formalized the concept. He bridged De Stijl, Bauhaus, and the beginnings of concrete art. His manifesto remains the cornerstone of the movement.

Otto G. Carlsund

A Swedish painter and critic, Carlsund moved steadily toward concrete art, eventually becoming one of its most faithful advocates. Although his group Art Concret had a short life, his works embodied the cerebral qualities of the style.

Max Bill

Perhaps the most influential figure in spreading concrete art beyond its origins, Max Bill was a Swiss architect, designer, and artist. He studied at the Bauhaus, later teaching and creating works that merged art with mathematics and physics. His “Endless Ribbon” sculptures exemplify the movement’s geometric purity.

Jean Hélion

Initially part of the Art Concret group, Hélion later shifted toward figurative painting. His brief involvement, however, illustrates how many artists of the era experimented with the movement before moving on.

The Movement Beyond Europe

Concrete art did not remain confined to Europe. After World War II, its principles traveled to Latin America, where they took root in new and dynamic ways.

-

Arte Concreto-Invención in Argentina (1945) pursued the ideal of art as a self-sufficient reality.

-

Grupo Madí, also in Argentina, explored irregular frames and playful geometry.

-

Neoconcrete movement in Brazil, led by artists such as Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, challenged the rigidity of European concrete art by incorporating movement, participation, and sensory experience.

These groups transformed concrete art into something more interactive and poetic, making it deeply influential in Latin American modernism.

Criticism and Challenges

Concrete art was often labeled as “cold” or “detached.” Critics argued that its rationalism made it inaccessible to the wider public. Unlike Cubism or Expressionism, which carried emotional or social resonance, concrete art could feel like an intellectual exercise, a closed system of forms speaking only to itself. This limited its mass appeal. While movements like Abstract Expressionism captured global attention with raw emotion, concrete art remained a more specialized, cerebral pursuit.

Legacy and Contemporary Influence

Despite its limitations, the movement’s influence is undeniable:

-

Op Art and Minimalism inherited its precision and geometric focus.

-

Graphic design and typography were transformed by its clarity and structural thinking, especially through Max Bill’s work in Swiss design.

-

Contemporary architecture and digital design continue to draw on its principles of grid, proportion, and reduction.

Artists such as François Morellet expanded its reach into conceptual and kinetic art, while Victor Vasarely used its ideas to create optical illusions that fascinated mass audiences. Even today, echoes of concrete art appear in UI design, fashion patterns, and abstract sculpture, proving that its visual language remains relevant.

Concrete Art: A Universal Language of Form

Concrete art may never have reached the popularity of Cubism or Expressionism, but it carved out a unique place in modern art history. It sought nothing less than a universal, timeless language of pure form and color a radical departure from centuries of art tied to representation and emotion. By stripping art down to its barest essentials, it challenged viewers to see beauty in geometry, balance, and precision. And though often considered “cold,” its influence continues to shape the visual world around us from galleries to the digital screens we use every day.

More soul, more stories, right this way:

- Forgiveness: A Wild Provocation from a Nonconforming Soul

- Creativity: Characteristics of Creatives

- Bohemian Rhapsody and Crime and Punishment: Two Souls, One Cry

- Artistic Expression: Why Art Matters

(FAQ)

1. What is the main idea behind concrete art?

Concrete art eliminates representation, focusing only on shapes, lines, and colors as autonomous elements.

2. How does concrete art differ from abstract art?

Abstract art often simplifies or distorts reality, while concrete art avoids reality altogether, creating forms with no external reference.

3. Who founded the concrete art movement?

Theo van Doesburg formally defined it in his 1930 manifesto The Basis of Concrete Art.

4. What are examples of concrete art today?

From Max Bill’s sculptures to UI design and minimalist architecture, its principles continue to influence contemporary aesthetics.

5. Why is concrete art sometimes called “cold abstraction”?

Because of its emphasis on precision and detachment from emotion, critics saw it as rational and mechanical, rather than expressive.

References

-

Theo van Doesburg, The Basis of Concrete Art, 1930.

-

Gaderian, D. Concrete Art in Europe Since 1945. Hatje Cantz, 2002.

-

Encyclopaedia of Art Education – Concrete Art: Definition, History, Artists.

-

Max Bill Foundation – Works and Writings.